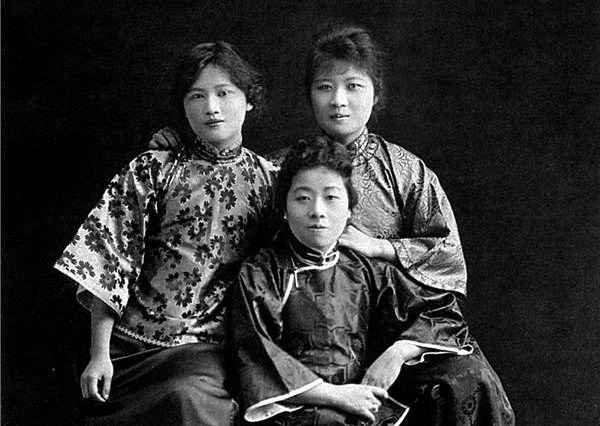

We’ve all heard about Jung Chang or at least about her best-selling novel Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (1991), which the Asian Wall Street Journal called “the most read book about China”. “Wild Swans” explores the lives of Chang’s grandmother, mother and herself in twentieth-century China. It was translated into 37 languages and sold 13 million copies. The book is particularly good at bringing a unique light on the female struggle in the modern world. The factual and emotionally unattached but deeply meaningful literary style in which hardship and political upheaval come together was certain to find a readership. That’s why every new Jung Chang book is an event in itself. The October 29, 2019, launch of Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China was no exception. Once again, Jung Chang brought the female experience into the spotlight, following the same recipe of the original best-seller: a group memoir of three women with very interesting lives. This time, instead of focusing on the uncommon lives of common people, Jung Chang introduces us to three extraordinary women who helped shape twentieth-century China.

When we think politically about China in the early 1900s, we might think about Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-Shek or Mao. When we switch the focus to the “women behind the men” we find the surname “Soong”. The sister’s lives spanned three centuries (May-ling died in 2003, age 105), always at the centre of action through a hundred years of wars, seismic revolutions and dramatic transformations. The backdrop moved from grand parties in Shanghai to penthouses in New York, from exiles’ quarters in Japan and Berlin to secret meeting rooms in Moscow, from the compounds of the Communist elite in Beijing to the corridors of power in democratising Taiwan. “The sisters experienced hope, courage and passionate love, as well as despair, fear and heartbreak. They enjoyed immense luxury, privilege and glory, but also constantly risked their lives” (Kindle Location 405).

As individuals, from the information available, they remained fairy tale figures, summed up by the much-quoted saying: “In China, there were three sisters. One loved money, one loved power, and one loved her country.”

Father Soong: From Wealth to Political Power

Nobody believed that twenty-three-year-old Emperor Guangxu was capable of conducting the country’s first modern war. Sun Yat-sen was particularly interested in that fact. “‘We must not miss this opportunity of a lifetime,’ he said to his friends. A plan was made. They would start a revolt in Canton and occupy the city; after this, which they termed the ‘Canton Uprising’, they would go on to seize other parts of China” (Kindle Location 571).

They wanted to pay gangsters to help them, but the massive undertaking was extremely expensive. Huge sums were needed to pay for the gangsters as well as weapons. Sun planned to go to America to raise more. At this juncture, a letter came from a friend in Shanghai. It urged him to return at once to start a revolution. China was suffering appalling defeats at the hand of the Japanese, and the Manchu regime was proving to be utterly incompetent and unpopular.

“The man who wrote the letter and helped trigger the republican revolution was Soong Charlie, a thirty-three-year-old former preacher for the American Southern Methodist Church and now a wealthy businessman in Shanghai. Charlie was the father of the three Soong sisters. At this time, his eldest daughter, Ei-ling, was five, and the youngest May-ling was not yet born. The middle daughter Ching-ling, who would eventually marry Sun—in spite of Charlie’s furious opposition—was a one-year-old baby. No one suspected that this affable and wealthy businessman and pillar of Shanghai society was an underground revolutionary” (Kindle Location 1005).

Red Sister, Ching-ling, married the ‘Father of China’, Sun Yat-sen, and rose to be Mao’s vice-chair.

Ching-ling had been interested in politics from her school days and by marrying the revolutionary figure that her father worshiped, Sun Yat-sen, she entered into the thick of the action. The relationship with Sun was always turbulent, as he had a bad temper and was absolutely focused on his goal of being China’s first Prime Minister.

‘“I didn’t fall in love,” Ching-Ling said slowly. “It was hero-worship from afar. It was a romantic girl’s idea when I ran away to work for him … I wanted to save China and Dr Sun was the one man who could do it, so I wanted to help him”’ (Kindle Location 1859).

Jung Chang’s views on historical personalities is one of deconstruction. She tells us all about the big veneration that Chinese people have for Sun Yat-sen as “The Father of China,” but by searching for data about his personal life, she humanizes the character and, eventually, show us some less immaculate sides. This is well represented in the episode where Sun’s mansion is being attacked by officer Ch’en and his troops: Sun escapes but leaves Ching-ling inside to take the cannons. He used his own wife as bait.

Ching-ling was at all Sun’s meetings with Moscow’s men, and came under the influence of Borodin. In the years to come, Red Sister stood as the most prominent dissident openly challenging Chiang’s regime, right under its nose in Shanghai. She gave whatever help the Chinese Communists asked for: transferring large sums of money to the CCP, or finding the right escorts to take their emissaries to Moscow.

At the age of fifty-six (eleven months older than Mao), Red Sister became the vice chairman of Mao’s government. When Mao proclaimed the People’s Republic on October 1, 1949, she walked right behind him through Tiananmen Gate. While her sisters were living as exiles, she was at the pinnacle of her life.

Little Sister, May-ling, Madame Chiang Kai-shek

The most cosmopolitan of the three sisters, May-ling highly appreciated luxury and life in the USA. She graduated from Wellesley with a major in English literature and a minor in philosophy.

May-ling arrived in Chongqing with Chiang in December 1938, after two months touring war fronts from the north to the south. She acted as a true wartime first lady, dealing with a million matters, exhausted but stimulated. Writing to her American friend Emma Mills, she exclaimed, “What a life! When the war is over I think my hair will turn white, but there is one comfort: I am working so hard I am not in danger of ever becoming a nice, fat, soft, sofa cushion, or having a derriere.” In another letter, again, “What a life! But we will not stop resisting” (Kindle Location 3423).

As Chiang became Generalissimo and leader of the Kuomintang, she had a chance to show her superior education as his English translator and advisor. Their relationship had its ups and downs, but Chiang treated her with respect and affection—as opposed to how Sun was to Ching-ling. During World War II, May-ling was essential to Chiang, building a legacy for her husband on par with Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin—all the international leaders who admired her manners and knowledge of both Eastern and Western cultures.

Although she demonstrated how much of a fighter she was, for exemple when standing strongly in Chongqing at her husband’s side in the war between the Nationalists and Communists, going trough wartime privations, or when when participating in political debate and high level negotiations, May-ling still had a reputation of being spoiled and addicted to an extravagant lifestyle.

In 1975, when Chiang Kai-shek was succeeded by his eldest son from a previous marriage, Chiang Ching-kuo, she emigrated from Taiwan to New York, where the Soong family owned expensive real estate and maintained an opulent lifestyle thanks to Ei-ling’s financial support. By the end of her life, May-ling had decided to just enjoy her privileges in the USA. At 103 years hold, she held an exhibition of her paintings in New York.

Ei-ling became Chiang’s unofficial main adviser and made herself one of China’s richest women.

Ei-ling was the provider for the sisters. She married H. H. Kung, who was the richest man in the early 20th century Republic of China. The couple would accumulate one of the greatest personal fortunes of 20th-century China. Ei-ling was well aware that she did much of the thinking for her husband—and that she exerted unparalleled influence over Little Sister and the Generalissimo.

During college she had an inclination for serious subjects and was well informed on recent history. Her last essay shows a political maturity beyond her nineteen years. Entitled “My Country and Its Appeal”, she commented on China’s cultural icon Confucius: “His grossest mistake was the failure to regard womankind with due respect. We learn from observation that no nation can rise to distinction unless her women are educated and considered as man’s equal morally, socially, and intellectually … China’s progress must come largely through her educated women” (Kindle Location 1138).

The author brings the female presence to the spotlight with significant success. The Soong sisters are known for belonging to the socialite, for the status quo and for being fashion icons of Shanghainese society in their time. Jung Chang shows us that these were fierce, intelligent women with political plans and ideas of their own.

In Chinese society, the Soong sisters are merely seen as shallow opportunists and it’s understandable how their opulent lifestyle might have invited that kind of resentment from the general population. However, Chang wants to show us that the male heroes of Chinese contemporary history were flawed and had precious help from others, including their rich wives. This point is clear and the perspective is definitely justified.

On the other hand, it is hard to escape the fact that these women gained importance through their association with powerful men. It was an association that they deliberately used to acquire political power and to shape their world according to their visions, but still a kind of power that couldn’t have been achieved on their own. The privilege of having a rich father that gave them an international education and introduced them to influential people is a class prerogative that can’t be discarded in favor of the narrative of personal success alone.

Jung Chang seems to be deconstructing many mythologies about important political figures, mostly Sun Yet-sen and Chiang Kai-shek. Her representation of a humanised biography of these characters is very well executed. They are not being humanised for the sake of empathy but mostly to expose how the disproportionate ambition of one individual can affect an entire nation. There are many details about these famous characters’ daily lives and the way they related with others, often revealing deceitful, unscrupulous behaviors. This is absolutely a counterculture perspective, unacceptable to the current regime. This underlying disruptive facet is one of the appeals of Chang’s writing, but it can also be seen as sectarian in her fervent anti-establishment approach. She supports her facts with extensive research and the bibliography is accessible in the end of the book, but it’s still difficult to draw the line between fact and fiction. We know that it’s not a fictional group biography, but as the documented events of the characters’ lives are presented in an entertaining manner, we might call it a fictionalized academic group biography. This leads to the construction of a narrative where the author is in constant appropriation of real historical figures’ lives, imbuing them with the author’s interpreted meaning and making it factual.

Having said that, Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister certainly challenges the perceptions we might have of history, ideology and gender. It’s a wonderful way to educate oneself in the history of modern China and understand the individual as well as the collective struggle required in social transformation.

Jung Chang 张戎 is the author of the best-selling books Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China (1991); Mao: The Unknown Story (2005, with Jon Halliday); and Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China (2013). Her works have been translated into more than 40 languages and sold more than 15 million copies worldwide. She has won many awards, including the UK Writers’ Guild Best Non-Fiction and Book of the Year UK, and has received a number of honorary doctorates from universities in the UK and USA (Buckingham, York, Warwick, Dundee, the Open University, and Bowdoin College, USA). She is an Honorary Fellow of SOAS University of London. Jung Chang was born in Sichuan Province, China, in 1952. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) she worked as a peasant, a “barefoot” doctor, a steelworker, and an electrician before becoming an English-language student at Sichuan University. She left China for Britain in 1978 and obtained a PhD in Linguistics in 1982 at the University of York—the first person from Communist China to receive a doctorate from a British university.

Sara F. Costa is a Portuguese poet. She has published five poetry collections that won several literary prizes in Portugal. She has an MA in Intercultural Studies: Portuguese/Chinese from Tianjin Foreign Studies University. Her verses have been translated into several languages and featured in literary journals across the world. As an emerging European poet, she was an invited author of the International Istanbul Poetry Festival 2017. In 2018, Sara worked in the organization of The Script Road-Macau Literary Festival and China-European Union Literary Festival in Shanghai and Suzhou. She translates Chinese poetry into Portuguese and is currently living in Beijing coordinating events for the Spittoon Beijing-based arts collective. She also hosts the bi-weekly Spittoon Poetry Workshop.